Greatest common divisor

In mathematics, the greatest common divisor (gcd), also known as the greatest common denominator, greatest common factor (gcf), or highest common factor (hcf), of two or more non-zero integers, is the largest positive integer that divides the numbers without a remainder. For example, the GCD of 8 and 12 is 4.

This notion can be extended to polynomials, see greatest common divisor of two polynomials.

Contents |

Overview

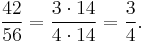

The greatest common divisor is useful for reducing fractions to be in lowest terms. For example, gcd(42, 56) = 14, therefore,

The greatest common divisor of a and b is written as gcd(a, b), or sometimes simply as (a, b). For example, gcd(12, 18) = 6, gcd(−4, 14) = 2. Two numbers are called coprime or relatively prime if their greatest common divisor equals 1. For example, 9 and 28 are relatively prime.

Calculating the gcd

Using prime factorizations

Greatest common divisors can in principle be computed by determining the prime factorizations of the two numbers and comparing factors, as in the following example: to compute gcd(18, 84), we find the prime factorizations 18 = 2 · 32 and 84 = 22 · 3 · 7 and notice that the "overlap" of the two expressions is 2 · 3; so gcd(18, 84) = 6. In practice, this method is only feasible for small numbers; computing prime factorizations in general takes far too long.

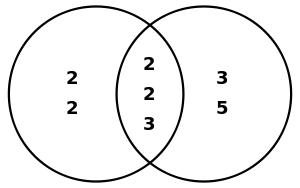

Here is another concrete example, illustrated by a Venn diagram. Suppose it is desired to find the greatest common divisor of 48 and 180. First, find the prime factorizations of the two numbers:

- 48 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3,

- 180 = 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5.

What they share in common is two "2"s and a "3":

- Least common multiple = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5 = 720

- Greatest common divisor = 2 × 2 × 3 = 12.

Using Euclid's algorithm

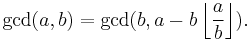

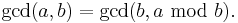

A much more efficient method is the Euclidean algorithm, which uses the division algorithm in combination with the observation that the gcd of two numbers also divides their difference: divide 84 by 18 to get a quotient of 4 and a remainder of 12. Then divide 18 by 12 to get a quotient of 1 and a remainder of 6. Then divide 12 by 6 to get a remainder of 0, which means that 6 is the gcd. Formally, it can be described as:

Which also could be written as

The series of quotients generated by the Euclidean algorithm composes a continued fraction.

Other methods

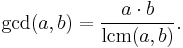

If a and b are not both zero, the greatest common divisor of a and b can be computed by using least common multiple (lcm) of a and b:

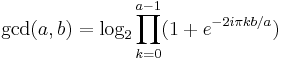

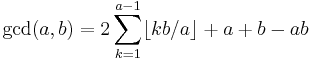

Keith Slavin has shown that for odd a ≥ 1:

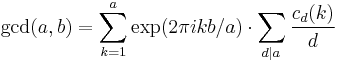

which is a function that can be evaluated for complex b [1] and Wolfgang Schramm has shown that

is an entire function in the variable b for all positive integers a where cd(k) is Ramanujan's sum.[2] Marcelo Polezzi has shown that:

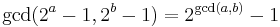

for positive integers a and b.[3] Donald Knuth proved the following reduction:

for non-negative integers a and b, where a and b are not both zero.[4]

Properties

- Every common divisor of a and b is a divisor of gcd(a, b).

- gcd(a, b), where a and b are not both zero, may be defined alternatively and equivalently as the smallest positive integer d which can be written in the form d = a·p + b·q where p and q are integers. This expression is called Bézout's identity. Numbers p and q like this can be computed with the extended Euclidean algorithm.

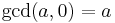

- gcd(a, 0) = |a|, for a ≠ 0, since any number is a divisor of 0, and the greatest divisor of a is |a|. This is usually used as the base case in the Euclidean algorithm.

- If a divides the product b·c, and gcd(a, b) = d, then a/d divides c.

- If m is a non-negative integer, then gcd(m·a, m·b) = m·gcd(a, b).

- If m is any integer, then gcd(a + m·b, b) = gcd(a, b).

- If m is a nonzero common divisor of a and b, then gcd(a/m, b/m) = gcd(a, b)/m.

- The gcd is a multiplicative function in the following sense: if a1 and a2 are relatively prime, then gcd(a1·a2, b) = gcd(a1, b)·gcd(a2, b).

- The gcd is a commutative function: gcd(a, b) = gcd(b, a).

- The gcd is an associative function: gcd(a, gcd(b, c)) = gcd(gcd(a, b), c).

- The gcd of three numbers can be computed as gcd(a, b, c) = gcd(gcd(a, b), c), or in some different way by applying commutativity and associativity. This can be extended to any number of numbers.

- gcd(a, b) is closely related to the least common multiple lcm(a, b): we have

-

- gcd(a, b)·lcm(a, b) = a·b.

- This formula is often used to compute least common multiples: one first computes the gcd with Euclid's algorithm and then divides the product of the given numbers by their gcd. The following versions of distributivity hold true:

- gcd(a, lcm(b, c)) = lcm(gcd(a, b), gcd(a, c))

- lcm(a, gcd(b, c)) = gcd(lcm(a, b), lcm(a, c)).

- It is useful to define gcd(0, 0) = 0 and lcm(0, 0) = 0 because then the natural numbers become a complete distributive lattice with gcd as meet and lcm as join operation. This extension of the definition is also compatible with the generalization for commutative rings given below.

- In a Cartesian coordinate system, gcd(a, b) can be interpreted as the number of points with integral coordinates on the straight line joining the points (0, 0) and (a, b), excluding (0, 0).

Probabilities and expected value

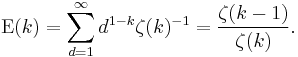

In 1972, J. E. Nymann showed that the probability that k independently chosen integers are coprime is 1/ζ(k).[5] (See coprime for a derivation.) This result was extended in 1987 to show that the probability that k random integers has greatest common divisor d is d-k/ζ(k).[6]

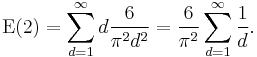

Using this information, the expected value of the greatest common divisor function can be seen (informally) to not exist when k = 2. In this case the probability that the gcd equals d is d−2/ζ(2), and since ζ(2) = π2/6 we have

This last summation is the harmonic series, which diverges. However, when k ≥ 3, the expected value is well-defined, and by the above argument, it is

For k = 3, this is approximately equal to 1.3684. For k = 4, it is approximately 1.1106.

The gcd in commutative rings

The greatest common divisor can more generally be defined for elements of an arbitrary commutative ring.

If R is a commutative ring, and a and b are in R, then an element d of R is called a common divisor of a and b if it divides both a and b (that is, if there are elements x and y in R such that d·x = a and d·y = b). If d is a common divisor of a and b, and every common divisor of a and b divides d, then d is called a greatest common divisor of a and b.

Note that with this definition, two elements a and b may very well have several greatest common divisors, or none at all. But if R is an integral domain then any two gcd's of a and b must be associate elements. Also, if R is a unique factorization domain, then any two elements have a gcd. If R is a Euclidean domain then a form of the Euclidean algorithm can be used to compute greatest common divisors.

The following is an example of an integral domain with two elements that do not have a gcd:

The elements 2 and 1 + √(−3) are two "maximal common divisors" (i.e. any common divisor which is a multiple of 2 is associated to 2, the same holds for 1 + √(−3)), but they are not associated, so there is no greatest common divisor of a and b.

Corresponding to the Bezout property we may, in any commutative ring, consider the collection of elements of the form pa + qb, where p and q range over the ring. This is the ideal generated by a and b, and is denoted simply (a, b). In a ring all of whose ideals are principal (a principal ideal domain or PID), this ideal will be identical with the set of multiples of some ring element d; then this d is a greatest common divisor of a and b. But the ideal (a, b) can be useful even when there is no greatest common divisor of a and b. (Indeed, Ernst Kummer used this ideal as a replacement for a gcd in his treatment of Fermat's Last Theorem, although he envisioned it as the set of multiples of some hypothetical, or ideal, ring element d, whence the ring-theoretic term.)

See also

- Coprime

- Least common multiple

- Lowest common denominator

- Binary GCD algorithm

- Euclidean algorithm

- Extended Euclidean algorithm

- Greatest common divisor of two polynomials

Notes

- ↑ Slavin, Keith R. (2008). "Q-Binomials and the Greatest Common Divisor". Integers Electronic Journal of Combinatorial Number Theory (University of West Georgia, Charles University in Prague) 8: A5. http://www.integers-ejcnt.org/vol8.html. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ↑ Schramm, Wolfgang (2008). "The Fourier transform of functions of the greatest common divisor". Integers Electronic Journal of Combinatorial Number Theory (University of West Georgia, Charles University in Prague) 8: A50. http://www.integers-ejcnt.org/vol8.html. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ Polezzi, Marcelo (1997). "A Geometrical Method for Finding an Explicit Formula for the Greatest Common Divisor". Amer. Math. Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 104 (5): 445–446. doi:10.2307/2974739. http://www.jstor.org/pss/2974739.

- ↑ Knuth, Donald E.; R. L. Graham, O. Patashnik (March 1994). Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-55802-5.

- ↑ J. E. Nymann, On the probability that k positive integers are relatively prime. Journal of Number Theory, 4:469–473, 1972.

- ↑ J. Chidambaraswamy and R. Sitarmachandrarao. On the probability that the values of m polynomials have a given g.c.d. Journal of Number Theory, 26:237–245, 1987.

Further reading

- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89684-2. Section 4.5.2: The Greatest Common Divisor, pp. 333–356.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Section 31.2: Greatest common divisor, pp. 856–862.

- Saunders MacLane and Garrett Birkhoff. A Survey of Modern Algebra, Fourth Edition. MacMillan Publishing Co., 1977. ISBN 0-02-310070-2. 1–7: "The Euclidean Algorithm."

External links

- greatest common divisor at Everything2.com

- Greatest Common Measure: The Last 2500 Years, by Alexander Stepanov

- Online gcd calculator

- HCF and LCM Calculator

- Online calculator - displays fractions of given numbers and supports more than 2 input numbers

- Computing the greatest common divisor at sputsoft.com

![R = \mathbb{Z}\left[\sqrt{-3}\,\,\right],\quad a = 4 = 2\cdot 2 = \left(1+\sqrt{-3}\,\,\right)\left(1-\sqrt{-3}\,\,\right),\quad b = \left(1+\sqrt{-3}\,\,\right)\cdot 2.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/063e7f57a200c9f2ed9f0b727885cc70.png)